It was sometime after midnight, and Michael Jordan was thirsty. He grabbed a Gatorade and headed to the checkout counter at a convenience store located in some unremarkable town. As he handed the drink to the cashier, he asked, "Is this your best-selling product?" No, the clerk said without looking up, Pepsis or Cokes were. Jordan seemed surprised, but paid his bill and returned to the team bus without the employee noticing that the curious customer resembled the basketball player on the promotional Gatorade cutout stationed a few feet away.

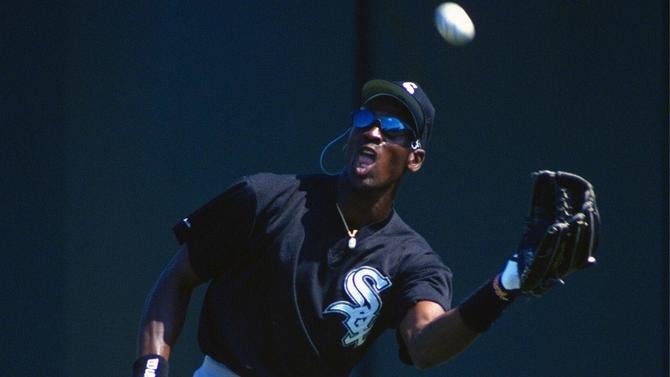

Jordan wasn't accustomed to going unnoticed in public. Then again, he wasn't used to many aspects of his life. It was 1994. He had walked away from the National Basketball Association, the league he had revolutionized on and off the court, to chase his baseball dreams.

He wasn't a Chicago Bull anymore; he was a Birmingham Baron, a member of the Chicago White Sox Double-A affiliate. His new teammates, mostly in their mid-20s, were thrilled. "It's hard to picture a better scenario for a Chicago kid," said Barry Johnson, a reliever for the Barons, "to be playing in the White Sox organization and teammates with Michael Jordan."

It's hard to picture a better scenario for revisiting Jordan's exodus to baseball than the present. Some 26 years later, ESPN has made it again chic to examine Jordan by airing "The Last Dance," a 10-part documentary that promises to examine him from every angle.

How much the program touches on Jordan's Birmingham detour is to be seen, but we took the opportunity to ask a couple former Barons: what was it like to play professional baseball with Michael Jordan?

Airspace with His Airness

Mike Bertotti, a left-hander who later pitched in parts of three seasons with the White Sox, remembers his first meeting with Jordan. The encounter came hours after a brush with the law.

The day prior, Bertotti had been promoted from High-A Prince William. Rather than leave his car in Virginia he opted to make the overnight drive. He was somewhere in North Carolina when his lead foot caught Johnny Law's attention. "I said, 'listen, sir, I apologize that I'm going a little fast. I gotta report to the Birmingham Barons baseball team, I just got promoted,'" he said. "I even showed him my White Sox equipment bag in my backseat. I said, 'I'm going to play with Michael Jordan. Obviously you know Michael Jordan.'

"I don't know if he believed me or not. Either way, he wrote me a ticket."

A lifelong New York Knicks fan, Bertotti knew plenty about Jordan. His team had been tormented by Jordan time and again. The 1993 Eastern Conference finals against the Knicks served as the penultimate series before Jordan announced his first retirement from the NBA. Jordan averaged 32 points, six rebounds, seven assists, and more than two steals over the six games. Although the Knicks won the first two games of the series, the Bulls took the final four to punch their ticket to the NBA Finals. Once there, Jordan and crew triumphed over the Phoenix Suns.

Most minor-league games begin at 7 p.m., give or take a few minutes, meaning players are required to be at the park by 3 p.m. Bertotti had arrived closer to midday. After meeting with manager Terry Francona, he had been guided to his locker by a clubhouse attendant. He was soaking in Double-A life when he noticed the nameplate on his neighboring locker: "JORDAN."

Bertotti, who admitted he developed butterflies after his discovery, figured his anxiousness would be eased by the arrival of other players. He did not expect that Jordan would be the first to arrive in the clubhouse, clocking in more than 90 minutes before check-in time. Jordan strolled up to Bertotti and introduced himself. "I was in awe, I'm like, 'Hi, Mr. Jordan, my name is Mike Bertotti. He's like, 'yeah, Michael Jordan,' I go, 'Yeahhh, I know who you are.'"

Everyone knew who Jordan was, but that didn't prevent him from fitting in. Both Johnson and Bertotti contend Jordan proved to be "one of the guys," or, at least, as much as he could be given his status as the world's foremost basketball player. He rode buses. He carried his own bags. He parked his own car. He was the first one in the dugout to offer a high-five.

Jordan, already renowned for his monomaniacal work ethic, endeared himself to his new teammates by accumulating sweat equity. "I prided myself on my work ethic and getting to the field and putting in work, and you could not beat him to the field," Johnson said. "He was there, taking extra batting practice before batting practice. We'd play our games, and he was the last one there, finishing up with Mike Barnett, our hitting coach. I'm sitting here thinking, from a dollars and cents standpoint, this guy does not need to work this hard."

Added Bertotti: "When I tell you he was there early every day, he was there early every day."

Between the lines

A cruel reality, of life and sport, is that hard work does not always precipitate good results.

Jordan's efforts to improve at baseball were appreciated, but they did not necessarily translate to his Baseball Reference page. In nearly 500 trips to the plate, he hit .202/.289/.266 with three homers and 30 steals. He walked a fair amount, more than 10 percent of the time, and that helped offset a strikeout rate nearing 23 percent. Jordan, to his credit, did fare better during his stint in the Arizona Fall League: he hit .252 with five extra-base hits and six steals.

Jordan's struggles were predictable. He was a 31-year-old who was more comfortable running a 2-on-1 than working a 2-and-1. The White Sox couldn't afford to put Jordan on a slow development path given his age, but they did him few favors by shipping him to Double-A. After all, Double-A is the ballplayer equivalent of the page-69 test: like what you see there, and you'll probably continue to like what you see.

For as athletic and ambitious as Jordan was, he couldn't make up the deficit against his more experienced peers. "You could see that some of the instinctive things were not quite there," Johnson said. Those issues carried over on defense. The Barons pitching staff even held meetings with Francona during which they lobbied for Jordan to move from right to left field. His elongated arm action sapped his arm strength and allowed baserunners to go first-to-third on routine balls hit his way. "We said, 'Tito, listen, you're killing us. Can you please put him in left field,'" Bertotti said. "He's like, 'well, it's really not my decision, it's coming from upstairs.'"

Growing pains notwithstanding, Jordan stuck with baseball. Johnson and Bertotti each praised his improvement during the season, an obvious byproduct of his natural athleticism and relentless drive to get better. Early on, Jordan was incapable of hitting mid-90s fastballs due to a long swing. Through his work with Barnett, he was able to make his swing more compact.

There were other adjustments Jordan had to make, too. He was used to having a hundred opportunities to impact a basketball game. In baseball, he would be the catalyst a handful of times, at most. After a multi-error game, Francona joked that Jordan "gets confused with basketball" because he "wants to be involved in every play."

Jordan's teammates advised him to become an active bystander. He listened. When he was in the dugout, he would study the opposing pitchers, looking for a physical or tactical tell that could be used to gain an advantage. Becoming a dedicated student of the game didn't turn Jordan stoic. He would still, following a particularly tough game, rant to a teammate: "Damn, you pitchers. What's with this slider? How in God's name do you hit this hard slider?"

Parting shots

An enduring question, even now, is whether Jordan would have reached the majors had he stuck with baseball. Not as a starting outfielder, but as a triple-threat: a reserve outfielder, box-office draw, and team-store cash cow.

"If you look at what he accomplished during the Birmingham season, and if you look at the season as a whole, you zero in on the batting average, but seeing what kind of production he did from the midway point on, and then going out to the Fall League and competing against everyone's top prospects and the numbers are even better," Johnson said. "Being with him on a daily basis for six months, and knowing how much work he was putting into it ... I don't think it's that big of a stretch to see him in a big-league uniform."

Even Jordan's fiercest critics acknowledged it was a distinct possibility. "Michael can't really play baseball, but he's not terrible," All-Star catcher John Stearns told an Arizona paper in late 1994. "He doesn't have power. His defense is way below average. He can't throw. His baseball instincts are poor. But he can run a little bit and can hit a little bit. Considering he's never played baseball all these years, it's incredible that he's able to hold his own here. He's not a prospect for me. But he may play in the big leagues. You may take him as a 25th guy. Why not?"

The answer to Stearns' question was revealed in early March 1995, when Jordan announced he was leaving baseball. The ongoing strike had, he said, "made it increasingly difficult to continue my development at a rate that meets my standard." Bulls coach Phil Jackson told the Associated Press that Jordan "needed the opportunity to get better," but that the "window was closing too quickly and he decided it wasn't going to happen for him." The strike ended on March 26, a week after Jordan had played in his first game back with the Bulls.

Jordan may have gone 21 months between NBA appearances, but he had continued to hoop during his hiatus. He played in pickup games with his Barons teammates throughout the season, and then partook in weekly runs during the Arizona Fall League.

Bertotti, listed at 6-foot-1, recalls a game where he attempted a 3-pointer over Jordan. He took the opportunity to let Jordan, a famed trashtalker, hear about it. "I said, 'Michael, you just let me shoot a 3-pointer over you? You got Defensive Player of the Year last year, and you just let me shoot a three-pointer over you?'"

Jordan responded to the ribbing by ratcheting up his intensity. The next time down, Jordan instructed Bertotti to guard him. "He's dribbling the ball, back and forth, and he's looking me in the eyes as he's dribbling. He's like, 'are you ready, are you ready?' I'm down in an athletic stance, and I'm saying I'm ready. Next thing I know, he did a crossover dribble and went past me and I didn't see him go by. His first step was that quick."

Months later, Jordan was using the same move to average 31.5 points per game in the playoffs, albeit as part of a run that saw the Bulls lose in the second round to the Orlando Magic.

One of the final acts of Jordan the Baseball Player came on the hardcourt, near the end of the Arizona Fall League. Normally reluctant to throw down during pickup games, he agreed to replicate his signature dunk from the free-throw line. By this point, word of Jordan's presence had lured a crowd of spectators, mostly children, hoping to see him for themselves. The players gladly cleared the runway, taking seats around the key. Jordan started at midcourt. He palmed the ball and sprinted toward the rim, leaping with his lead toe on the line. He elevated, soared, and finished with the grace and intensity forever captured on posters and sneakers.

"He was, like, walking on air," Bertotti said. Then he was gone.